The Story of SeaWorld Trainer Dawn Brancheau and Captive Orca Tilikum

February 24, 2010, started as any other day would at SeaWorld, Orlando.

Hundreds of families flocked to the theme park, eager to see the main attraction: impressive 22.5 feet, 12,500-pound orcas putting on a show for them.

While this day started out normally for senior trainer Dawn Brancheau, it would end sadly. Her beloved Tilikum, at that time the largest orca in captivity, turned on her as she lay talking to him.

While this day started out normally for senior trainer Dawn Brancheau, it would end sadly. Her beloved Tilikum, at that time the largest orca in captivity, turned on her as she lay talking to him.

He dragged her by her ponytail into the water, thrashing her around so vigorously that she sustained terrible injuries before drowning.

The story is tragic for many reasons. Not only did Dawn adore Tilikum, but it seemed he was immensely fond of her, too.

The crowds that gathered to watch the trainer and orca that day were subject to a terrifying sight: the 40-year-old being dragged to her demise.

Then, there’s the tale of the captive creature, who’d been kept isolated for human entertainment for decades.

This is the story of Dawn Brancheau and how her untimely passing shone a newfound light on the marine park industry.

Dawn’s Love Of Marine Life

Born in April 1969 in Cedar Lake, Indiana, Dawn was the youngest of the six LoVerde siblings.

Her love for sea life was cemented after a family holiday to Orlando, where she saw a show involving Shamu, one of the first-ever captive orcas.

After the show, Dawn decided when she grew up, she wanted to be a Shamu trainer at SeaWorld.

Although she’d never get to train Shamu—she sadly passed in the early 1970s—Dawn’s love for whales would never leave her.

She obtained a degree in animal behavior from the University of South Carolina and embarked on a career working with sea life.

She began by working with dolphins before securing her dream job at SeaWorld in 1994, training sea lions.

It wasn’t just sea life Dawn loved, but all animals. She rescued dogs, rabbits, ducks, and chickens when she wasn’t at work. At any given time, her home was often filled with animals she was rehabilitating.

While working at SeaWorld Orlando, Dawn was introduced to stunt water skier Scott Brancheau, whom she would date and later marry in 1996.

That year would be a big one for Dawn; not only did she get married, but she also got a promotion at work. She finally got to train orcas, something she’d been dreaming of since she was a little girl.

Keeping up with the orcas was no easy feat. In fact, to ensure she was fit enough to give the orcas the intensity required to train them, Dawn kept a rigorous fitness routine.

This involved cycling, heavy weights, and running regular marathons. After all, wild orcas swim anywhere between 40 and 150 miles per day.

The captive whales had a lot of energy they were unable to expel in captivity, so their trainer had to have superior fitness to at least try and match their stamina.

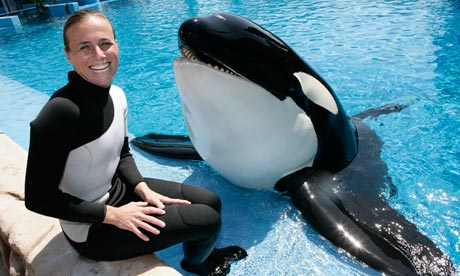

As the years went by, Dawn became something of a celebrity.

She was, quite literally, SeaWorld’s poster child, with her face adorning many of the theme park posters and banners. She appeared on TV shows, gave interviews, and became part of the attraction itself.

Her clear love for the orcas and her ability to interact with the whales was joyous for the public to see, though even Dawn would admit it wasn’t without its dangers.

Sadly, on February 24, 2010, those dangers became very real.

The Day Of The Incident

That fateful day, Dawn had successfully completed her “Dine with Shamu” show alongside other trainers.

The crowd, as they always did, applauded the spectacle: after all, Dawn had interacted with a 12,000-pound male orca, guiding Tilikum around the pool as they ate their buffet.

That was the premise of the show: guests would eat their meals as they watched the orcas eat their meals and perform tricks.

Little did the cheering crowd know that Tilikum had a ruthless past. In fact, he had been responsible for multiple human fatalities over his years in captivity.

The first was in 1991, when Keltie Lee Byrne, a 20-year-old Canadian animal trainer, slipped into the whale pool. One of the orcas grabbed her leg and wouldn’t let go. The other whales, including Tilikum, prevented anyone from rescuing Keltie.

Then, in 1999, 27-year-old Daniel Dukes, an unhoused man from South Carolina, hid in SeaWorld premises until the park closed. He decided to climb into Tilikum’s pool. Daniel’s body was found the next day, floating in the water.

Dawn, of course, was aware of Tilikum’s previous aggressive behaviors, though her relationship with him made her feel safe and in control when working with him.

It’s been said the trainer loved the whale, and in turn, he, too, felt affection for Dawn. As far as many were concerned, it was a heartwarming display of human-animal connection that few others could ever achieve.

However, the SeaWorld audience in Orlando that day would soon be confronted with the idea that Tilikum wasn’t a domesticated orca who preferred life in captivity. Despite being captured as a calf in 1983, he was still very much a wild apex predator.

Since he’d been held captive for decades, he didn’t know how to communicate with other whales, nor did he get to roam the ocean and hunt for prey.

For reasons unknown, he chose Dawn as his prey that fateful February afternoon.

After the performance, Dawn fed Tilikum fish as she conversed with the crowd. She sat by the pool, and suddenly, the orca lunged toward her, grabbed her ponytail, and dragged her underwater.

After the performance, Dawn fed Tilikum fish as she conversed with the crowd. She sat by the pool, and suddenly, the orca lunged toward her, grabbed her ponytail, and dragged her underwater.

Dawn was no match for the whale, who began thrashing her about repeatedly.

Other trainers tried to stop him, distracting him with food or using nets to put an end to the attack. The attempts were fruitless. For 30 minutes, he kept Dawn in his clutches.

Her injuries were a testament to just how brutal the attack was: her spinal cord had been cut. Her ribs and jawbone had been broken, and her knees dislocated. Horrifically, her scalp had been torn off.

The audience bore witness to much of the attack taking place.

After a half-hour standoff, Tilikum eventually released Dawn and was ushered into a smaller pool.

Dawn’s body was recovered, and the subsequent autopsy found she’d passed from drowning and blunt force trauma.

Spectators were shocked, perhaps unaware that these wild animals were capable of such ferociousness.

While the event was awful for Dawn and her bereft family, it was also a catalyst for opening up the conversation about the welfare of marine mammals in captivity.

The Aftermath

The shock and outrage of Dawn’s passing went far beyond SeaWorld Orlando, sparking public outcry, heavy media coverage, and a never before considered discourse as to how marine parks truly operate.

There was no denying that the attack on Dawn wasn’t an isolated incident and was preventable.

There was no denying that the attack on Dawn wasn’t an isolated incident and was preventable.